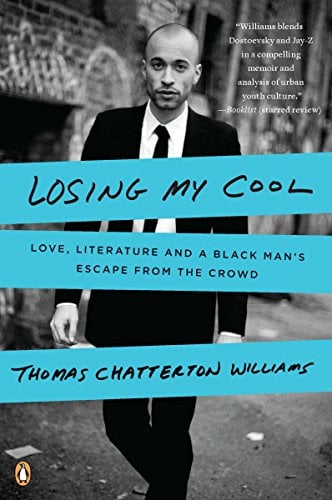

Losing My Cool: Love, Literature, and a Black Man's Escape from the Crowd / Williams, Thomas Chatterton

| List Price: | |

Our Price: $17.99 | |

|

For Bulk orders

| |

|

Used Book Price: | |

| Losing My Cool: Love, Literature, and a Black Man's Escape from the Crowd / Williams, Thomas Chatterton | |

| Publisher: Penguin Books | |

| Availability:In Stock. | |

| Sales Rank: 308039 | |

|

Similar Books

Listen to Thomas Chatterton Williams's annotated playlist, a lineup of ten essential hip-hop tracks that informed Losing My Cool, including highlights from Dr. Dre, 2pac, and Jay-Z.

Listen to Thomas Chatterton Williams's annotated playlist, a lineup of ten essential hip-hop tracks that informed Losing My Cool, including highlights from Dr. Dre, 2pac, and Jay-Z. Browse the playlist

Q: Tell us a little bit about yourself.

I grew up in New Jersey, but my parents are from out west. They moved the family to New Jersey when my father, a sociologist by training, took a job in Newark running anti-poverty programs for the Episcopal Archdiocese. My father “Pappy” who is black, is from Galveston and Fort Worth, Texas. My mother, who is white, is from San Diego. They both lament the decision to move east.

I spent the first year of my life in Newark, but was raised in Fanwood, a solidly middle-class suburb with a white side and a black side. We lived on the white side of town mainly because Pappy, who had grown up under formal segregation, refused out of principle to ever again let anyone tell him where to live.

I studied philosophy at Georgetown University in Washington D.C., and more recently, attended graduate school at New York University.

Q: Why did you write this book?

I started writing this book out of a searing sense of frustration. It was 2007, hip-hop had sunk to new depths with outrageously ignorant artists like the Dip Set and Soulja Boy dominating the culture and airwaves, and something inside me just snapped. I was in grad school at NYU and one of my teachers gave the class the assignment of writing an op-ed article on a topic of choice, the only requirement being to take a strong stand. I went straight from class to the library and in three or four hours banged out a heartfelt 1000 words against what I saw as the debasement of black culture in the hip-hop era. After some revisions, the Washington Post published what I had written and it generated a lot of passionate feedback, both for and against. I realized that there was a serious conversation to be had on this subject and that there was a lot more that I wanted to say besides. That was why I started.

By the time I finished writing, though, it had become something quite different, something very personal, a tribute to my father and to previous generations of black men and women who went through unimaginable circumstances and despite that, or rather because of it, would be ashamed of the things we as a culture now preoccupy ourselves with, rap about, and do on a daily basis.

Basically, the book began as a Dear John letter to my peers and ended as a love letter to my father.

Q: You fully embraced the black culture of BET and rap superstars starting at a young age. What drew you in?

I think I was drawn to black culture by the same things that have been drawing the entire world to it since the days of Richard Wright, Josephine Baker and Louis Armstrong. This culture is original, potent and seductive. As we all know, the evil of slavery and the sting of the whip have given us many things including the voice of Nina Simone, the prose of James Baldwin, the Air Jordan sneaker, the blues, jazz, moonwalking, and more recently gangsta rap.

What matters here is not that I found the black hip-hop driven culture that I was surrounded by alluring—that’s not significant, unique or particularly interesting. The crucial point is that this culture exerted a seriously negative influence on my black peers and me, and it did so in a way and to a degree that it didn’t for non-blacks. The main reason for this, I firmly believe, is that we (blacks) tended to approach hip-hop seriously and earnestly, striving to “keep it real” and viewing a lifestyle governed by hip-hop values as some kind of prerequisite to an authentically black existence. Non-blacks were better able to embrace hip-hop with a healthy sense of irony.

Q: Your father tutored you throughout your life, yet you still seem awed that you escaped the allure of hip-hop culture. Where are your high school classmates today?

Yes, I was and still am awed! Let’s be honest, like many committed parents my father faced daunting odds getting me away from the foolishness that surrounded us. Because we were not wealthy and living in seclusion, it was basically him and my mother against a neighborhood and high school of bad role models who were working in conjunction with a relentless and powerful propaganda campaign that streamed into the house 24/7 via Hot 97 FM, Black Entertainment Television and MTV. The odds were that his message would be drowned out in a cacophony of bullshit.

To answer the second question—and to be precise, we’re just talking about blacks and Latinos when we talk about my classmates here because I wasn’t really around anyone else in those days—I haven’t kept up with any of the classmates I mention in the book with the exception of Charles, who is like a brother to my brother and me and a son to my parents. Charles is doing fantastic, having recently graduated from one of the top two law schools in the country.

From what I hear and occasionally see on Facebook, no one else has done anything close to that. That’s sad to me because there were many other students who were intelligent enough to go that far, but they didn’t. Without my father’s encouragement and guidance, of course, I don’t think that Charles and I would have gone far either. The culture was stifling. None of us (except for one or two good girls who come to mind, but who were not influential at all on the rest of us) considered being smart very “real.” Most of the others that I mention in the book seem to be in solidly mediocre positions, having grown into adults with varying degrees of success. Some have done okay, but some have utterly failed. Some are happily married and some still dream of becoming rappers, which floors me. The girls seem to have done better than the boys. Are they all a bunch of criminals and crackheads? No, not at all, and I want to emphasize that. But was there a lot of needlessly squandered potential? Yes, absolutely.

Q: Your father owned 15,000 books, but says that he has never read for enjoyment. What is the difference between your attitude toward books and your father’s?

It’s true, Pappy is in his 70s and to this day he still underlines articles in the newspaper every morning. My father loves to read, but he can’t simply relax with a good book. Reading will always be work for him. He always felt pressure to read for the purpose of obtaining practical knowledge (even from novels). He was born black in the segregated south in the 1930s, and he figured out early on that if he didn’t teach himself what he needed to know through books no one else would. I contrast this with my own view that it’s nice to enjoy literature for purely aesthetic reasons.

In college and in my early 20s, I read for the latter reason mainly, for beauty and quixotic epiphany, both of which are valuable things, but a bit luxurious, too. Today, as a writer and someone who cares deeply about sentences, I find myself reading for many more practical reasons than I used to. I read for technical and inspirational knowledge about my craft. In that way I am more like my father than I used to be. However, I’m also always on the lookout for beauty for beauty’s sake and nothing more. I see it both ways now.

Q: In the book you describe Georgetown as “an outpost of white and international privilege” nestled into one of our country’s blackest cities. What was your attitude going into your first year? And upon graduating?

Georgetown is certainly that. Going into my first year, my attitude was essentially that I would be an alien there; at most I would just be passing through. I had no animosity toward the wider non-black world, I just couldn’t imagine myself reflected in it. It wasn’t real to me. By the time I graduated, I had become a stranger to the hip-hop culture I had grown up in. Crucially, though, I didn’t feel that I had started selling out or acting white at all. Actually, I felt prouder than ever to be black—it’s just my definition of what black could be had begun to expand dramatically.

Q: At different points in Losing My Cool, you identify hip-hop as “a culture,” “a way of being in the world,” as like a religion, an “opiate,” “captor,” “nation,” and, well, just music. What does hip-hop signify to you today?

For a lot of people I know, hip-hop is still all of those things, so it signifies all of that to me still. In my own life, though, more than anything, hip-hop is now the sound of my childhood and adolescence. It signifies the past and not the future. Of course, anything that reminds you of your growing up years is going to be special to you in certain ways, but I see hip-hop, by its very nature, as basically an obstacle to serious engagement with the world.

Q: Do Kanye, Jay-Z, and other current rap superstars have anything to offer society?

The thing I want to stress here is that it has never been my aim or desire to criticize hip-hop from a musical or formal standpoint. For one thing, I’m not qualified to do that, and for another, I’m already convinced that it is formally very interesting and worthy of respect from a variety of perspectives.

So with that said, yes, I do think artists like Jay-Z and Kanye West especially have something to offer society, and that is the spectacle of their talent. These are extraordinarily talented cats. Jay-Z’s wordplay on songs like “D’Evils” or “Can I Live?” surpasses what most Harvard and Yale graduates can do with language. As for Kanye West, he’s got to be one of the most gifted and original popular musicians of his generation in any genre. The things he hears you and I don’t hear.

It’s no secret that we all love to discover and marvel at talent, put it on a pedestal and gawk at it. But in my opinion, what these guys do for us seldom or never gets any deeper than merely displaying that they are clever, and doing so in strictly solipsistic ways. In terms of their ethics, interests, values, and the lyrical content of their work, these rappers have very little that is enriching and lots that is actually very damaging to offer their listeners. They engage us in a catchy way so we admire them for it, and hunger after what they produce, but it’s empty calories at best. The truth is that there’s very little that is nutritious to consume there. You can gain far more from an hour spent with Joan Didion or James Baldwin than with Jay-Z, period.

Q: How does your father feel about Losing My Cool?

My father named me after a writer, always encouraged me to be a writer, and worked extremely hard to equip me with the tools to become one, so this book is my way of saying thanks to him and I think he gets that. The first time he read the book I was nervous, though, because he’s an intensely private man and here I was writing a memoir and exposing things about myself that he might find vulgar or embarrassing. Unlike with my mother and brother, I never let him read the manuscript; I waited until I had galleys before I shared it with him. When I finally gave him a copy, he took it upstairs to his reading room and read the whole thing straight through. And he took notes on it! He identified two minor factual errors in the text, which was really helpful. Other than that, he didn’t say much immediately about it, we just sat down and watched some NFL, but I knew that he was very happy because he was in a really playful mood throughout the game, laughing and joking with my mother and me.

Since then he’s read the book cover to cover at least three more times, underlining it extensively (always underlining!). We’ve spoken a lot about the more philosophical subject matter, which comes up later in the book, like Heidegger’s idea that groups rob the individual of him or herself. This is an important point for my father. Pappy is almost never in crowds, and he doesn’t belong to any scene and never has. That’s because, he says, he’s been trying his whole life to define himself and not be defined by others. I think he’s proud that I was able to touch on this.

Q: Is there anything you’d like to go back and tell your low slung jeans-wearing, basketballing, game-running former self?

Most definitely! I’d say: Life is long and the world is wide, so it’s important as hell to guard against making choices that pointlessly limit you down the road. And also, it’s better to be open and flexible than closed and hard. And also, when you’re tall and slim, it’s much, much more flattering to the physique to wear clothes that fit. And also—pay more attention in French class, please!

Q: What can we do to overcome the negative aspects of hip-hop culture such as self-hatred, emphasis on failure, willful ignorance?

The first thing we have to do is get serious. The world is a serious place—the climate is changing and we are at war—and way too many of us are walking around worrying about utter trivialities, such as what 50 Cent said about Rick Ross or what shoes Kanye West wore.

In the book, I describe a time in my early high school years when I was playing basketball with members of the St. Anthony Friars, one of the best, if not the best, boy’s varsity teams in the nation. These kids there were dedicated to the game of basketball the way many black kids I know are dedicated to hip-hop, to such an extent it is almost unbelievable if you take a step back and think about it. In fact for young black men hip-hop and playing sports, particularly basketball, go hand-in-hand. What’s heartbreaking to me is that if these kids had ever put similar effort into developing their minds, some of them would now be inventing ways to combat global warming, some would be curing cancer, and one or two would be writing the next great American novel. Almost none of the members of the Friars team, if any, now play in the NBA, so what was it all for?

The second thing is that we really have to expand our idea of what it means to be black. Being authentically black has to mean something much more than merely being cool, athletic, sexy, thugged-out, from the ‘hood, or “real.” To that end, I think the election of Barack Obama was earth-shattering and we will start reaping the tangible rewards five, ten, fifteen, twenty years down the road. At least, that is what I sincerely wish for.

Q: What do you hope readers will take away from Losing My Cool?

I hope that Losing My Cool will provoke readers black, white, old and young to question, critique, and ultimately reject more of the nonsense and conformity that surrounds us all.

(Photo of Thomas Chatterton Williams © Luke Abiol)

Now you can buy Books online in USA,UK, India and more than 100 countries.

*Terms and Conditions apply

Disclaimer: All product data on this page belongs to

.

.No guarantees are made as to accuracy of prices and information.